How to Use Models

JButton), for example,

has a model (a ButtonModel object)

that stores the button's state —

what its keyboard mnemonic is,

whether it's enabled, selected, or pressed,

and so on.

Some components have multiple models.

A list (JList), for example,

uses a ListModel

to hold the list's contents,

and a ListSelectionModel

to track the list's current selection.

You often don't need to know about the models

that a component uses.

For example, programs that use buttons

usually deal directly with the JButton object,

and don't deal at all with the ButtonModel object.

Why then do models exist? The biggest reason is that they give you flexibility in determining how data is stored and retrieved. For example, if you're designing a spreadsheet application that displays data in a sparsely populated table, you can create your own table model that is optimized for such use.

Models have other benefits, too.

They mean that data isn't copied between

a program's data structures

and those of the Swing components.

Also, models automatically

propagate changes to all interested listeners,

making it easy for the GUI to stay in sync with the data.

For example, to add items to a list

you can invoke methods on the list model.

When the model's data changes,

the model fires events to

the JList and any other registered listeners,

and the GUI is updated accordingly.

Although Swing's model architecture is sometimes referred to as a Model-View-Controller (MVC) design, it really isn't. Swing components are generally implemented so that the view and controller are indivisible, implemented by a single UI object provided by the look and feel. The Swing model architecture is more accurately described as a separable model architecture. If you're interested in learning more about the Swing model architecture, see A Swing Architecture Overview, an article in The Swing Connection.

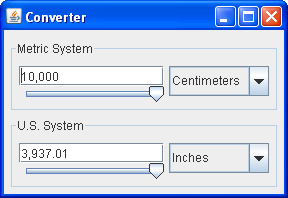

An Example: Converter

This section features an example called Converter, which is an application that continuously converts distance measurements between metric and U.S. units. You can run Converter ( download JDK 6). Or, to compile and run the example yourself, consult the example index.As the following picture shows, Converter features two sliders, each tied to a text field. The sliders and text fields all display the same data — a distance — but using two different units of measure.

The important thing for this program

is ensuring that only one model

controls the value of the data.

There are various ways to achieve this;

we did it by deferring to the top slider's model.

The bottom slider's model

(an instance of a custom class called FollowerRangeModel)

forwards all data queries to the top slider's model

(an instance of a custom class called ConverterRangeModel).

Each text field is kept in sync with its slider,

and vice versa,

by event handlers that listen for changes in value.

Care is taken to ensure that the top slider's model

has the final say about what distance is displayed.

When we started implementing the custom slider models,

we first looked at

the API section of

How to Use Sliders. It informed us that all slider data models must

implement the BoundedRangeModel interface.

The

BoundedRangeModel API documentation tells us

that the interface has an implementing class named

DefaultBoundedRangeModel.

The

API documentation for DefaultBoundedRangeModel shows that it's a general-purpose implementation

of BoundedRangeModel.

We didn't use DefaultBoundedRangeModel

directly because it stores data as integers,

and Converter uses floating-point data.

Thus, we implemented

ConverterRangeModel as a subclass of

Object.

We then implemented FollowerRangeModel

as a subclass of ConverterRangeModel.

For Further Information

To find out about the models for individual components, see the "How to" pages and API documentation for individual components. Here are some of our examples that use models directly:

- All but the simplest of the table examples implement custom table data models.

- The color chooser demos

have change listeners on the color chooser's selection model

so they can be notified when the user selects a new color.

In ColorChooserDemo2, the

CrayonPanelclass directly uses the color selection model to set the current color. - The

DynamicTreeDemo

example sets the tree model

(to an instance of

DefaultTreeModel), interacts directly with it, and listens for changes to it. - ListDemo

sets the list data model

(to an instance of

DefaultListModel) and interacts directly with it. - SharedModelDemo

defines a

SharedDataModelclass that extendsDefaultListModeland implementsTableModel. AJListandJTableshare an instance ofSharedDataModel, providing different views of the model's data. - In the event listener examples,

ListDataEventDemo creates and uses a

DefaultListModeldirectly. - Our spinner examples create spinner models.

- As you've already seen, the Converter example defines two custom slider models.